Chapter 6. Magnetostatic Fields in Matter

6.1. Magnetization

Any macroscopic object consists of many atoms or molecules, each having

electric charges in motion. With each electron in an atom or molecule we can

associate a tiny magnetic dipole moment (due to its spin). Ordinarily, the

individual dipoles cancel each other because of the random orientation of their

direction. However, when a magnetic field is applied, a net alignment of these

magnetic dipoles occurs, and the material becomes magnetized. The state of

magnetic polarization of a material is described by the parameter M which

is called the magnetization of the material and is defined as

M = magnetic dipole moment per unit

volume

In some material the magnetization is parallel to

.

These materials are called paramagnetic. In other materials the magnetization

is opposite to

.

These materials are called diamagnetic. A third group of materials, also called

Ferro magnetic materials, retain a substantial magnetization indefinitely after

the external field has been removed.

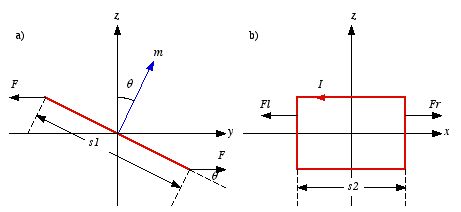

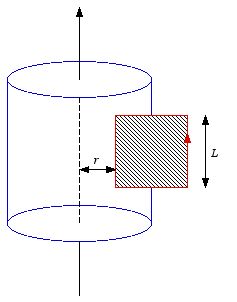

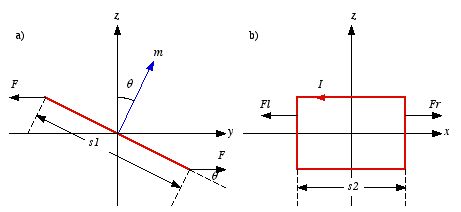

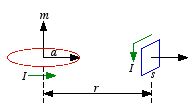

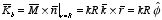

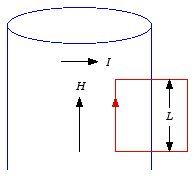

Figure

6.1. Force on a rectangular current loop.

Figure

6.1. Force on a rectangular current loop.

6.1.1. Paramagnetism

Consider a rectangular current loop, with sides s1 and

s2, located in a uniform magnetic field, pointing along the

z axis. The magnetic dipole moment of the current loop makes an angle

θ with the z axis (see Figure 6.1a). The magnetic forces on

the left and right sides of the current loop have the same magnitude but point

in opposite directions (see Figure 6.1b). The net force acting on the left and

right side of the current loop is therefore equal to zero. The force on the top

and bottom part of the current loop (see Figure 6.1a) also have the same

magnitude and point in opposite directions. However since these forces are not

collinear, the corresponding torque is not equal to zero. The torque generated

by magnetic forces acting on the top and the bottom of the current loop is equal

to

The magnitude of the force F is equal to

Therefore, the torque on the current loop is equal to

where

is the magnetic dipole moment of the current loop. As a result of the torque on

the current loop, it will rotate until its dipole moment is aligned with that of

the external magnetic field.

In atoms we can associate a dipole moment with

each electron (spin). An external magnetic field will line up the dipole moment

of the individual electrons (where not excluded by the Pauli principle). The

induced magnetization is therefore parallel to the direction of the external

magnetic field. It is this mechanism that is responsible for

paramagnetism.

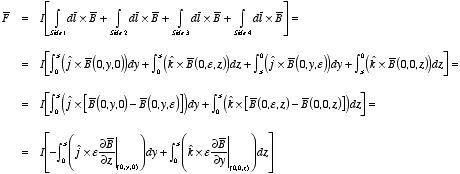

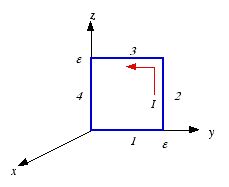

In a uniform magnetic field the net force on any current loop

is equal to zero:

since the line integral of

is equal to zero around any closed loop.

If the magnetic field is

non-uniform then, in general, there will be a net force on the current loop.

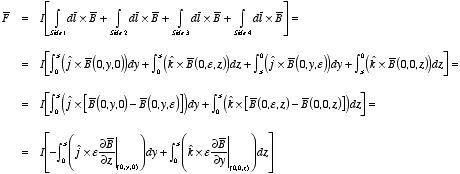

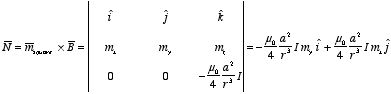

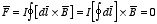

Consider an infinitesimal small current square of side

ε, located in

the

yz plane and with a current flowing in a counter-clockwise direction

(see Figure 6.2). The force acting on the current loop is the vector sum of the

forces acting on each side:

Figure

6.2. Infinitesimal square current loop.

Figure

6.2. Infinitesimal square current loop.In this derivation we have used a first-order Taylor expansion of

:

and

Assuming that the current loop is so small that the derivatives of

are constant over the boundaries of the loop we can evaluate the integrals and

obtain for the total force:

where

m is the magnetic dipole moment of the current loop. In this

derivation we have used the fact that the divergence of

is equal to zero for any magnetic field and this requires that

The magnetic dipole moment m of the current loop is equal

to

Therefore, the equation for the force acting on the current loop can be

rewritten in terms of

:

Any current loop can be build up of infinitesimal current loops and

therefore

for any current loop.

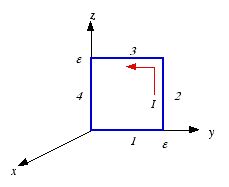

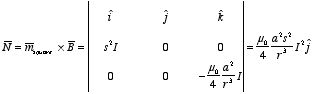

Example: Problem 6.1.

a) Calculate

the torque exerted on the square loop shown in Figure 6.3 due to the circular

loop (assume r is much larger than a or s).

b) If the

square loop is free to rotate, what will its equilibrium orientation

be?

a) The dipole moment of the current loop is equal to

where we have defined the z axis to be the direction of the dipole.

The magnetic field at the position of the square loop, assuming that

r»a, will be a dipole field with θ =

90°:

The dipole moment of the square loop is equal to

Figure

6.3. Problem 6.1.

Figure

6.3. Problem 6.1.Here we have assumed that the x axis coincides with the line

connecting the center of the current circle and the center of the current

square. The torque on the square loop is equal to

b) Suppose the dipole moment of the square loop is equal to

The torque on this dipole is equal to

In the equilibrium position, the torque on the current loop must be equal

to zero. This therefore requires that

Thus, in the equilibrium position the dipole will have its dipole moment

directed along the z axis. The energy of a magnetic dipole in a magnetic

field is equal to

The system will minimize its energy if the dipole moment and the magnetic

field are parallel. Since the magnetic field at the position of the square loop

is pointing down, the equilibrium position of the current loop will be with its

magnetic dipole moment pointing down (along the negative z

axis).

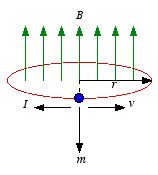

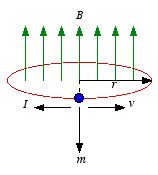

6.1.2. Diamagnetism

Consider a very classical picture of a Hydrogen atom consisting of an

electron revolving in a circular orbit of radius r around a nucleus (see

Figure 6.4). Suppose that the velocity of the electron is equal to v.

Since the velocity of the electron is very high, the revolving electron looks

like a steady current of magnitude

Figure

6.4. Electron in orbit.

Figure

6.4. Electron in orbit.The direction of the current is in a direction opposite to that of the

electron. The dipole moment of this current is equal to

If the atom is placed in a magnetic field, it will be subject to a torque.

However, it is very difficult to tilt the entire orbit. Instead the electron

will try to reduce its torque by changing its velocity. With no magnetic field

present, the velocity of the electron can be obtained by requiring that the

centripetal force is sustained by just the electric force:

In a magnetic field, the centripetal force will be sustained by both the

electric and the magnetic field:

Here we have assumed that the magnetic field is pointing along the positive

z axis (in a direction opposite to the direction of the magnetic dipole

moment). We have also assumed that the size of the orbit (r) does not

change when the magnetic field is applied. Combining the last two equations we

obtain

or

Assuming that the change in the velocity is small we can use the following

approximations:

and

Therefore,

This equation shows that the presence of the magnetic field will increase

the speed of the electron. An increase in the velocity of the electron will

increase the magnitude of the dipole moment of the revolving electron. The

change in

is opposite to the direction of

.

If the electron would have been orbiting the other way, it would have been

slowed down by the magnetic field. Again the change in the dipole moment is

opposite to the direction of

.

In

the presence of an external magnetic field the dipole moment of each orbit will

be slightly modified, and all these changes are anti-parallel to the external

magnetic field. This is the magnetism that is responsible for diamagnetism.

Diamagnetism is present in all materials, but is in general much weaker than

paramagnetism. It can therefore only be observed in those materials where

paramagnetism is not present.

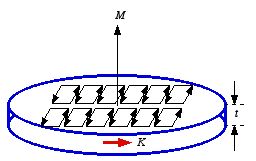

6.2. The Field of a Magnetized Object

Consider a magnetized material with magnetization

.

The associated vector potential

is equal to

Following the same procedure used in Chapter 4 to calculate the

electrostatic potential of a polarized material, we obtain for

:

where

is the bound volume current and

is the bound surface current. If the material has a uniform magnetization then

the bound volume current is zero. The field produced by a magnetized object is

equal to the field produced by the bound currents.

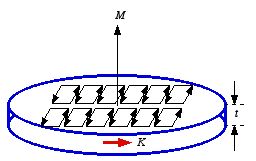

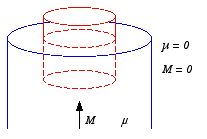

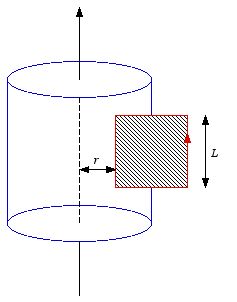

Figure

6.5. Bound surface current.

Figure

6.5. Bound surface current. Consider a uniformly magnetized thin slab of material of thickness

t. The material can be cut up into tiny current loops (see Figure 6.5).

If each current loop has an area a then the dipole moment due to a

surface current I is equal to

The volume of the current loop is at and therefore its dipole moment

must be equal to

This requires that the surface current of the current loop is equal

to

Since the magnetization is uniform, the current in each of the current

loops will be constant and flowing in the same direction. Therefore, all volume

currents cancel, and the only current remaining will be a surface current,

flowing on the surface of the material. The current flowing on the surface of

the material will be equal to the current in each of the current loops.

Therefore, the current density on the surface is equal to

In vector notation:

This equation is also consistent with the fact that there is no current

flowing on the top and bottom surfaces (where

).

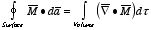

Example: Problem 6.7

An infinitely long circular cylinder carries a uniform magnetization

parallel to its axis. Find the magnetic field (due to

)

inside and outside the cylinder.

Consider a coordinate system

S

in which the

z axis coincides with the axis of the cylinder. The

magnetization of the material is equal to

Since the material is uniformly magnetized, its bound volume current is

equal to zero. The bound surface current is equal to

This current distribution is identical to the current distribution in an

infinitely long solenoid. The magnetic field outside an infinitely long

solenoid is equal to zero (see Example 9, Chapter 5 of Griffiths), and therefore

also the field outside the magnetized cylinder will be equal to zero. The

magnetic field inside an infinitely long solenoid can be calculated easily using

Ampere's law (see Example 9, Chapter 5 of Griffiths). It is equal to

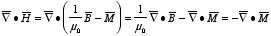

6.3. The Auxiliary Field H

The magnetic field in a system containing magnetized materials and free

currents can be obtained by calculating the field produced by the total current

where

This approach is very similar to the approach taken in electrostatics where

the total electric field produced by a system containing dielectric materials is

equal to the electric field produced by a charge distribution σ

where

To calculate the magnetic field produced by a system containing magnetized

materials we have to use the following form of Ampere's law:

This equation can be rewritten as

The quantity in parenthesis is called the H-field

plays a role in magnetostatics analogous to

in electrostatics. Ampere's law in terms of

reads

and

Ampere's law for

tells us that the curl of

is equal to the free current density. However, a knowledge of the free current

density is not sufficient to determine

.

The Helmholtz theorem shows that besides knowing the curl of a vector function,

we also need to know the divergence of that vector function before it is

uniquely defined. Although the divergence of

is zero for any magnetic field (and therefore Ampere's law for

defines

uniquely) the divergence of

is not necessarily zero:

Therefore, only for those systems where

can we use Ampere's law for

directly to calculate

.

The divergence of

will be zero only for systems with cylindrical, plane, solenoidal, or toroidal

symmetry.

The

field is a quantity that is used in the laboratory more often that the

field. This is a result of the dependence of

on only the free currents (which are easy to control). The

field depends both on the free and on the bound currents, and thus requires a

detailed knowledge of the magnetic properties of the materials used. In

electrostatics, the electric field can be obtained immediately from the

potential difference (which is easy to control). The electric displacement

depends only on the free charge distribution, but in most cases a direct

measurement of the free charge distribution is very difficult to carry out.

Therefore, in electrostatics the electric field is in most cases a more useful

parameter then the electric displacement

.

Example: Problem 6.12

An infinitely long cylinder, of radius R, carries a "frozen-in"

magnetization, parallel to the axis,

where

k is a constant and

r is the distance from the axis

(there is no free current anywhere). Find the magnetic field inside and outside

the cylinder by two different methods:

a) Locate all the bound currents, and

calculate the field they produce.

b) Use Ampere's law to find

,

and then get

.

a) The

magnetization of the material is directed along the

z axis and is equal

to

The bound volume current is equal to

The bound surface current is equal to

Figure

6.6. Problem 6.12.

Figure

6.6. Problem 6.12.The bound currents produce a solenoidal field. The field outside the

cylinder will be equal to zero and the field inside the cylinder will be

directed along the

z axis. Its magnitude can be obtained using Ampere's

law. Consider the Amperian loop shown in Figure 6.6. The line integral of

along the Amperian loop is equal to

The current intercepted by the Amperian loop is equal to

Ampere's law can now be used to calculate the magnetic field:

b) The divergence of

is equal to zero. Therefore, Ampere's law uniquely defines

.

The

field is pointing in the

z direction. Using Ampere's law, in terms of

the

field, we immediately conclude that for the Amperian loop shown in Figure

6.6

since there is no free current This can only be true if

.

This implies that

Therefore, the magnetic field

is equal to

In the region outside the cylinder the magnetization is equal to zero and

therefore the magnetic field is equal to

In the region inside the cylinder the magnetization is equal to

and therefore the magnetic field is equal to

which is identical to the result obtained in part a).

Example: Problem 6.14

Suppose the field inside a large piece of material is

,

and the corresponding

field is equal to

a) A small spherical cavity is hollowed out of the material. Find the

field at the center of the cavity in terms of

and

.

Also find the

field at the center of the cavity in terms of

and

.

b) Do

the same for a long needle-shaped cavity running parallel to

.

c) Do

the same for a thin wafer-shaped cavity perpendicular to

.

Assume

the cavities are small enough so that

,

,

and

are essentially constant.

a) The field in the spherical cavity is the

superposition of the field

and the field produced by a sphere with magnetization

.

The bound volume current in the sphere is equal to zero (uniform magnetization).

The bound surface current is equal to

Here we have assumed that the magnetization of the sphere is directed along

the z axis. Now consider a uniformly charged sphere, rotating with an

angular velocity ω around the z axis. The system carries a

surface current equal to

Comparing these two equations for the surface current we conclude

that

In Example 11 of Chapter 5 the magnetic field produced by a uniformly

charged, rotating sphere was calculated. The magnetic field inside the sphere

was found to be uniform and equal to

But since

we can rewrite this expression as

The magnetic field inside the spherical cavity is therefore equal

to

The corresponding

field is equal to

Here we have used the fact that

since no materials are present there.

b) The magnetic field inside the

needle-shaped cavity is equal to the vector sum of the field

and the field produced by a needle-shaped cylindrical piece of material with

magnetization

.

The field inside a needle-shaped cylinder of magnetization

is approximately equal to the field inside an infinitely long solenoid. This

field was calculated in Problem 6.7, and for a cylinder with a uniform

magnetization

it is equal to

The magnetic field inside the needle-shaped cavity is thus equal

to

The corresponding

field is equal to

c) The magnetic field in the center of a thin wafer-shaped cavity is equal

to the vector sum of

and the magnetic field inside a waver-shaped material with magnetization

.

Since the thickness of the wafer approaches zero, the total surface current on

the material approaches zero, and consequently the magnetic field inside the

waver approaches zero. Therefore, the magnetic field inside the cavity will be

equal to

The corresponding

field is equal to

6.4. Linear Media

In paramagnetic and diamagnetic materials, the magnetization is maintained

by the external magnetic field. The magnetization disappears when the field is

removed. Most paramagnetic and diamagnetic materials are linear; that is their

magnetization is proportional to the

field:

The constant of proportionality

is called the magnetic susceptibility of the material. In vacuum the magnetic

susceptibility is zero. In a linear medium, there is linear relation between

the magnetic field and the

field:

where

is called the permeability of the material. The permeability of free space is

equal to

.

The

linear relation between

and

does not automatically imply that the divergence of

is zero. The divergence of

will only be equal to zero inside a linear material, but will be non-zero at the

interface between two materials of different permeability. Consider for example

the interface between a linear material and vacuum (see Figure 6.7). The

surface integral of

across the surface of the Gaussian pillbox shown in Figure 6.7 is definitely not

equal to zero. According to the divergence theorem the surface integral of

is equal to the volume integral of

:

Figure

6.7. Interface of linear materials.

Figure

6.7. Interface of linear materials.Therefore, if the surface integral of

is not equal to zero, the divergence of

can not be zero everywhere.

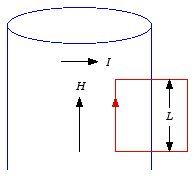

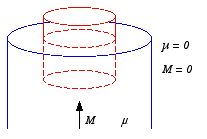

Example: Example 6.3

An infinite solenoid (N turns per unit length, current I) is

filled with linear material of susceptibility χm. Find

the magnetic field inside the solenoid.

Figure

6.8. Example 6.3.

Figure

6.8. Example 6.3. Because of the symmetry of the problem, the divergence of

will be equal to zero, everywhere. Therefore, the

field can be obtained directly from Ampere's law. Consider the Amperian loop

shown in Figure 6.8. The line integral of

around the loop is equal to

where the line integral is evaluate in the direction shown in Figure 6.8,

and it is assumed that the

field is directed along the

z axis. The free current intercepted by the

Amperian loop is equal to

Ampere's law for the

field immediately shows that

The magnetic field inside the solenoid is equal to

The magnetization of the material is equal to

and is uniform. Therefore, there will be no bound volume currents in the

material. The bound surface current is equal to

This last equation shows that the bound surface current flows in the same

direction (paramagnetic materials) or in an opposite direction (diamagnetic

materials) as the free current.

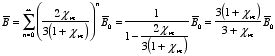

Example: Problem 6.18

A sphere of linear magnetic material is placed in an originally uniform

magnetic field

.

Find the new field inside the sphere.

This problem can be solved using a

method similar to the method used in example 7 of Griffiths (Chapter 4). The

external field

will magnetize the sphere:

This magnetization will produce a uniform magnetic field inside the sphere

(see Example 6.1 of Griffiths, Chapter 6):

This additional magnetic field magnetizes the sphere by an additional

amount:

This additional magnetization produces an additional magnetic field inside

the sphere:

The total magnetic field inside the sphere is therefore equal to

When can check the consistency of this answer by calculating the

magnetization of the sphere:

The magnetic field inside the sphere due to the magnetization

is equal to

The total magnetic field inside the sphere is therefore equal to

which is consistent with our assumption.

6.5. Nonlinear Media

The best known nonlinear media are the ferromagnetic materials.

Ferromagnetic materials do not require external fields to sustain their

magnetization (therefore, the magnetization definitely depends in a nonlinear

way on the field). The magnetization in ferromagnetic materials involves the

alignment of the dipole moments associated with the spin of unpaired electrons.

The difference between ferromagnetic materials and paramagnetic materials is

that in ferromagnetic materials the interaction between nearby dipoles makes

them want to point in the same direction, even when the magnetic field is

removed. However, the alignment occurs in relative small patches, called

domains. When a ferromagnetic material is not located in a magnetic field, the

dipole moments of the various domains are not aligned, and the material as a

whole is not magnetized. When the ferromagnetic material is put into a magnetic

field, the boundaries of the domain parallel to the field will increase at the

expense of neighboring boundaries. If the field is strong enough, one domain

takes over the entirely, and the ferromagnetic material is said to be saturated

(all unpaired electrons are aligned and therefore the magnetization reaches a

maximum value). The magnetic susceptibility of ferromagnetic materials is

around 103 (roughly eighth orders of magnitude larger than the

susceptibility of paramagnetic materials). When the magnetic field is removed

some magnetization remains (and we have created a permanent magnet). For any

ferromagnetic material, the magnetization depends not only on the applied

magnetic field but also on the magnetization history. The alignment of dipoles

in a ferromagnet can be destroyed by random thermal motion. The destruction of

the alignment occurs at a precise temperature (called the Curie point). When a

ferromagnetic material is heated above its Curie temperature it becomes

paramagnetic.